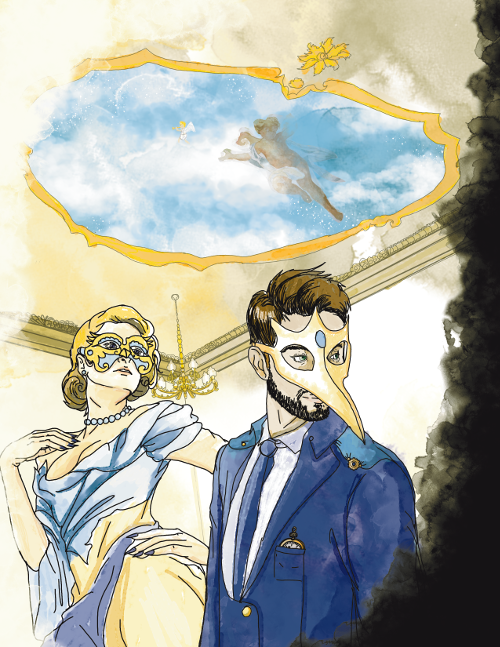

Captain Bleck chuckled, his broad chest shaking within the tight confines of his dress uniform.

“That’s what we want you women to believe,” he replied, a teasing edge just audible in his voice. “But don’t you think it for a moment. Why, in Burma, in ‘62…”

The party had overflown the ballroom. Couples strolled along the twilight paths, keeping discrete distances from one another. The night had reached that familiar stage of mild inebriation when the taut edges were beginning to wear off formal manners. Lucy knew this moment well. It was the part she always dreaded - the part her sisters all seemed to like so much - and she wasn’t sure how much longer she would be able to avoid all the depressingly eligible young men.

“Oh, you military men are all the same,” protested Anne, and Lucy stifled a yawn, because she had heard her sister use that phrase at least three times tonight already - to three different (but equally beastly-looking) men. There was so much conceit there it made her want to scream; but the men seemed to like it well enough.

Lucy wanted to leave her discrete little seat in the gazebo - she was quite sure that horrid little man from the Admiralty had spotted her - could feel him looming up behind - but when she got up to go, she saw it was a stranger.

“Oh,” said Lucy, the barbed remark dying on her lips as she realised she has no idea who this man was at all.

He was an odd fellow - thin, and jagged, somehow, though not unpleasant-looking. He looked very out of place amongst the well-to-do of society, and Lucy was suddenly struck by the thought that she would much rather spend time with this stranger than with any of the many people here whom she had known most her life.

“Oh,” replied the man, blinking at her with large , watery eyes, then gazing off into the murk as if there was something far more exciting there than the dimly-visible form of the creeping wisteria.

“Who are you?” Asked Lucy, half-hating herself for being interested enough to ask. She made a point of never, ever, asking anyone anything at one of mother’s dreadful parties.

The angular man waved a hand vaguely in the air.

“No-one important,” he muttered, pleasantly enough, not coming close to meeting her eye...

“Precisely, yes,” said the angular man. “Well, I would expect as much. That would account for the gradient.”

He wasn’t rude. Not exactly. But there was something about his polite indifference which made Lucy rather cross. After all, she was the one who was usually politely indifferent to everyone else. Having someone else do it to her seemed fundamentally back to front, somehow.

“Are you from the ministry?” she asked, finding she wanted to skewer his attention, if only so she could dismiss him once she had won it, thus returning things to their rightful order.

“Hah!” Exclaimed the angular man, still not looking at her. “You might say that.”

He really did seem tremendously interested in that bit of darkness. Much more interested than he was in - just for example - her. Not that he should be interested in her. Not at all. And yet…and yet, she had to admit, she was rather used to the attention. Perhaps she was more fond of that than she would like to admit. Now there was an uncomfortable thought…

“Mummy had it planted last year,” she said, gazing at the wisteria and trying - failing - to muster a shred of interest. “She caused it to be planted after daddy died,” she added, a shade maliciously, for she couldn’t say she really missed her father - had scarcely known him - and yet had discovered how profoundly uncomfortable comments like this could be for other people when effectively deployed.

“Hmm,” said the angular man, entirely unmoved.

That was it - the man’s complete lack of compassion for her imaginary loss was the final straw: she was Intrigued.

“Why,” she asked, with some irritation, “are you so bloody interested in - oh!”

This last came out in a gasp, for all of a sudden, Lucy saw something.

Something other than darkness, and quite different from the dim shape of the wisteria.

She saw - quite distinct, and quite, quite far off - people.

Lots of people.

A great many.

They were dressed in odd clothes - bedraggled and besmirched, tattered and torn from head to toe - and they were in peril, real peril, she was quite sure of it, though from what source exactly the peril threatened she found she really could not say.

She stuttered, tried to speak, found her tongue was tied.

“But…but all the pale people!” She managed to exclaim at last.

And then - for the very first time since they had met - the angular man really looked at her. His big watery eyes seemed to swivel, to fix on her at last.

“You see them?” He asked her, quiet but very intense.

She nodded vigorously, almost not trusting herself to say a word - for she did indeed see them, tens of people, a hundred maybe - all spectral and far off as if from a great distance, and yet amazingly sharp and clear.

They were shouting now, screaming and calling out, and she felt sure they were desperate to get her attention. And yet she could hear not a sound - not a sound, other than the rather tiresome hum of the party around her in the garden. And then, no one else in the garden seemed to be able to so much as see the little group. No one was paying the many little figures a shred of attention - no one accept Lucy, and the angular man, of course.

“How deeply unusual,” the angular man said.

Lucy nodded vigorously. The appearance of maybe a hundred spectral visitors in her wisteria did indeed qualify as unusual.

“Not them,” he clarified, nodding to the figures. “Such poor things are depressingly common, in these sad times.”

They did look like poor things. That seemed just right to Lucy. They weren’t just sad though, she realised, and nor were they upset - they were terrified, mortally terrified. And seeing their terror, Lucy felt a stab of it slice into her own heart.

“What’s…?” She started to ask, then realised that there was no time, no time at all. For something was happening to the figures. Even as she watched, the darkness lapped higher against them, lapped like dark water rising, and she understood.

“They’re drowning!” She exclaimed. “They’re all at sea!”

A few of the other party goers were giving Lucy odd glances now. She imagined briefly what she must look like, how wild and strange to be staring so intently into the darkness. But she found she did not care about that, not at all.

“We must help them!” She cried, and then Anne was gliding from one side, taking her arm firmly - and not all that kindly - and hissing in her ear something she did not care to catch.

“But look, Anne!” Lucy protested. “Just look, won’t you!”

Captain Bleck was beside her now, too, and several other braying military types behind him. They seemed a touch kinder than her sister, but it was a kindness that was just one thin degree from patronisation, and Lucy misliked it immensely.

The figures were falling fast now, the dark water rushing up, their faces desperate, their eyes staring, imploring, begging.

And Lucy wanted to help, but she could no more help the tiny figures than she could overcome whatever wilful blindness kept her sister and the others from seeing them.

They were falling.

Even as she watched, a girl - a girl no older than Lucy herself - was swallowed up by some unseen enormity in the darkness, vanishing beneath the freezing swell.

“Come on,” said Anne, and there was a calm, severe fury in her words now - a severe fury at her selfish, idiotic sister who was ruining the party for her. “You’ve said quite enough.”

Anne’s hand clasped tight on Lucy’s shoulder, and it was suddenly too much.

“Stop!” Shrieked Lucy. “Get back! Stop! Stop!”

And then she was blinking and breathing hard, because Anne had done just that.

Everything was silent. Everyone was still.

Lucy’s desperate eyes moved from her sister to the frozen, immobile bulk of Captain Bleck, and back again.

The world had indeed come to a dead halt.

In the darkness beyond the wisteria, the few last figures had stopped their desperate writhing. They were as still as paintings, though quite horribly lifelike in their terror and distress.

“Stop,” echoed Lucy, but softly now, an automatic noise.

“Yes,” agreed the little angular man. “Yes, we have.”

His eyes weren’t quite fixed on her, but Lucy had the feeling that the odd little man was looking at her quite intently; was looking at her much more intently, in fact, than he had been before when he had been idly talking to her.

“You did that,” she said after a moment. It wasn’t a question.

“I did,” he replied solemnly. “Well, I would have to go back over things, anyway. When I’m writing up my report.”

“Your report, is it?” Lucy said. She peered at the drowning figures. How many were left now? Could they still be saved, she wondered?

“Sometimes you have to let things play out several times,” the little man added, a shade defensively. He shrugged. “Then again, maybe not. I’ve seen this sort of thing depressingly often, you know.”

Lucy shuffled forward. She reached a hand into the darkness, tentative. As her flesh seemed to pass through the tiny, luminous figures, she felt the faintest fission, tingling, sparkling feeling, like sunlight on frozen skin. And yet she couldn’t touch them, not really.

“They need help,” said Lucy firmly. “They need help, and you just watch them?”

“Oh, they do!” The odd little man agreed, a passion in his voice which surprised her, for she had not heard it there before. “More than you can imagine! But what can I do? I’m not really here, you see. My compassion is meaningless. Only someone…”

And then he cut off, his eyes staring intently at the little figures, though Lucy felt quite sure he was really looking at her.

“Only someone who…what?” Lucy wondered aloud, then she shook her head as something else he had said caught up with her. “What do you mean, you’re not really here?”

She prodded him in the chest, harder than she might have.

“Ow,” he commented.

“Seem pretty real to me,” she muttered, carefully not apologising.

“That’s one way of looking at it,” he sniffed.

“Pretty convincing way of looking at it,” she replied, resisting the urge to prod him somewhere other than the chest.

“Yes, touch is convincing,” he replied. “But does it mean that I’m really here? Or does it mean that you…?”

He trailed off meaningfully, and Lucy felt herself redden. How instantly she knew what he was getting at! She thought of the endless procession of parties her mother threw, of receptions, of how sodden with boredom and hypocrisy they had always seemed to her; and of how little she had fitted into their world.

And this little man had wandered in from - from where? Wherever it was he had come from, he had seen it all in a moment; seen it all without ever really seeming to look at her.

She was an outsider in her own family. An outcast amongst her own set. An alien, misliked, unwanted; resentful.

And then, as quick as that torrent of thoughts had come to her, the further implication of his words were sinking in.

Her eyes darted to her fingers, to where they fluttered against those distant, disturbingly clear figures, to where their pale faces flashed with incandescent brilliance just beyond the confines of her world.

Just beyond? And yet, if they were beyond…how could she feel the echo of their presence? How could she feel them, sliding against the very tips, the very threshold of her flesh?

“That’s right,” he said, very quietly. And when she gave him a sharp look, she saw that though he was still apparently not watching her, that there was a silent attentiveness to him, a sense of a breath being held.

Her lips moved, and she almost found herself asking what he meant. But to do so would have been disingenuous. She knew what he meant, knew it with perfect clarity.

And to ask…well, that would just be another way of giving into her fears, her hesitations, her lack of faith - in herself, as well as (in a larger sense) in her family.

Her family whom she had always felt disconnected from, for almost as long as she could remember; felt embarrassed by; felt shame for.

But did they deserve that shame? Ultimately, it would be easier to assume they did, and then not have to test them.

Not to have to test herself.

She took a deep breath.

Lucy did not know how she knew it, how she suddenly understood - and yet, there it was: she could almost touch them, almost touch those tiny, desperate, helpless figures. And if it was almost, then perhaps…

Lucy let go. Let go of a breath, and let go of her shame, and let go - just a fraction - of the world she had always inhabited.

And she moved.

She moved without moving, and almost became just about.

For a moment, it was like sunlight again, a wave of sunlight splashing over her fingers. A moment later, she felt it for what it was: skin. The slack skin of a cold, lifeless hand. Then - with a thunderous pulse, and with a rushing sensation like a last, desperate surge towards some far-off surface, the hand clasped back.

For a moment, Lucy teetered on the edge. Some conflict was being fought within her, some decision, some impulse perfectly balanced between the ease of letting go, and the pain of holding on.

Lucy made her choice.

She tumbled backwards, sprawling, shoving her sister and the Captain away from her, in a space suddenly alive again with chatter and noise, censure and scorn.

Whatever she had done, Lucy had some how caused the angular man’s freezing of time to come unstuck.

She lay sprawling on the grass, the partygoers looking down on her in astonishment.

Her hand held something cold and wet.

She understood this at the same moment as she registered the weight on her body, and at the same instant she understood the soft, damp something pressed against her chin was hair.

She had pulled one of the figures.

She had plucked them out of the darkness.

She had saved them.

Lucy looked down.

A girl.

A little girl of maybe six, stared up at her with dark eyes.

The girl was shivering, convulsing. Her skin was cold and tinged with blue. Her hair smelt of salt.

“Lucy!” Said Anna, and though her voice sounded scandalised - as if Lucy had done the most dreadful thing imaginable - there was something else in her voice now, a hesitation, a lack of conviction.

Lucy ignored her.

She pulled herself up. She was shaking too, as if the little girl’s shivering were contagious. But it wasn’t fear Lucy felt now.

It was hope.

“Are you…?” Lucy murmured, looking closely at the girl, then hugging her tight.

She pulled back.

The girl only stared. She was looking around, a stunned wildness in those dark eyes. All around, the partygoers were staring back, unsure what to do.

Then Lucy noticed the girl’s leg, and she knew exactly what to do.

Clutching the girl’s leg, another hand held tight. A thin, wiry, blue-tinged hand, and an arm extending away from it into the darkness behind the wisteria…

“Lucy?” Said Anna again.

There was still an echo of distain there, though much of it had melted away, replaced with puzzlement and with…with something Lucy was most unused to hearing there.

Lucy blinked in the darkness, and thought how odd it was to hear her sister sound sad.

Not just sad - heartbroken. Utterly, utterly heartbroken - as if all the unhappiness in the world had suddenly crashed on her shores, as if the stern foundations of her life were suddenly crumbling.

“But…but where did she come from?” Anna went on.

And again, Lucy thought she sounded like her heart might break.

But Lucy shook her head, and shot her sister a dark look.

“Not ‘she’,” Lucy corrected. “‘They.’”

She indicated the girl’s leg, and when Anna frowned again, looking as if her sadness wanted to scuttle away again into comfortable obscurity, Lucy reached out and placed her sister’s hand firmly on the hand which extended from the darkness.

Anna jerked, as if she would pull away. Lucy held her tight.

“Help me!” Lucy hissed, staring at her sister, staring so intently, daring her to refuse.

Anna made a gasping noise; a soft noise, no more.

But when Lucy looked again, there were tears in her sister’s eyes.

Anna nodded. She looked away.

Then Lucy let out her breath, and the two sisters pulled together.

They heaved, and out of the darkness a second figure came, tumbling up from the place where the wisteria hung in the sultry summer’s air. And when the second thin, dark figure lay panting on the grass, when all around the partygoers looked on in amazement and disbelief, she suddenly understood.

She understood, because she saw at last what she had never noticed before.

She saw that the distain, the arrogance, the cruelty - all the foul things she found in her family and her set, had found in the whole world - those were just masks, too. They were as much masks as the braying bravado of the Captain Blecks, as the disingenuous eye-fluttering of all the poor, lost Annas.

They were all lost, she realised.

They were all lost little children, all terrified that someone would notice, all desperate to convince everyone else that they were not.

The braying and eye-fluttering, the worldly laughter and the cruelty: it was all an act.

The night had been torn open by the arrival of these people, and it did not matter where they came from or how it had come to pass. What mattered was that Lucy had pulled one of them through; and by peeling back the world, the spell those poor idiots had cast on themselves had been broken; the machinery of it all lay exposed, bleeding on the lawn.

And in that frayed moment, Lucy understood she had a chance, and she knew what she must do.

“Help them!” She commanded.

Her voice sounded thin in the fragrant night, and for a horrible moment she thought it would not work. She imagined them turning to look at her, the masks of scorn growing back so swiftly that in a moment they would forget once more that masks they even wore.

And then Anna made a noise.

It was somewhere between a sob and a shout, and the eyes her sister turned on her were her old eyes - the eyes Lucy knew from when they were children, before scorn or propriety had a chance to fester there - and then she was lunging forward, hurling her body into the darkness behind the wisteria…and when she came back, in her arms she held another child.

And that was all it took.

All at once, everyone was moving.

Soldiers were throwing down their smart coats, were crawling on their hands and knees, were pressing into the darkness and coming back carrying shivering, sodden forms.

It all happened in utter silence, and with an intensity that was more real than any word Lucy had heard uttered at any of mother’s dreadful parties.

Lucy smiled.

Already there were more dark figures on the lawn than she had seen in that last frozen glimpse. And more were being retrieved every moment. It was…

“Magnificent,” observed a voice from her elbow, and Lucy turned to see the small, angular man.

He was looking directly at her at last.

Lucy hesitated, but the work was proceeding without her. The grass under the wisteria had already degenerated into mud, each retrieved figure was soaked in salt water, and the whole of the lawn seemed in real danger of transforming into a small sea.

“Mother will be irked,” muttered Lucy, but even as she said it, she saw her mother working there amid the others, mud staining her splendid dress. Somehow, she looked better for it.

“How…how did you know?” The small man asked. “That they would help, I mean.”

Lucy shrugged.

“I didn’t,” she said. “I’m surprised they did help.”

They were silent for a moment.

A hubbub of voices was rising now, rising from the darkly drenched figures. Lucy could not understand the words, of course, but she felt sure she understood the tone.

Hope.

From the very jaws of despair: hope.

“You know,” she said, “you’re not really from the ministry at all. Are you?”

The little man shrugged.

“I’m from a ministry,” he told her. “People need ministries, you know. There are always people fleeing. And there are always people who do not - who will not - see. Sometimes we cannot do much. Sometimes we can only…only bear witness. But, just occasionally…”

He trailed off.

“I see” said Lucy.

He looked at her, really looked at her.

“You know,” he said after a moment. “I think maybe you do.”

A sudden stab of sadness clutched at her.

She wondered what her father would have done. She had never given him a chance, she realised.

Would he be on the ground now, scrabbling away like her mother, trying - trying at long last - to do something real?

Lucy liked to think he would.

She would never know…but then, she could hope, too.

She could imagine.

She shook herself.

There was work that needed doing.

There always was.

The End

If you liked this story, please consider sharing.

There is a limited edition NFT of this story, or rather there will be if anyone wants one...

The beautiful art is by ShadowSantos.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed